If we want to be successful at gardening or raising crops, and most of us do, there are some things that can make us much more efficient and successful. Explaining potential ways to maintain a seed book and field/yield notes takes a lot longer than actually doing it, happily. Both tracking seeds and their results and separating seeds in storage can help limit some of the pains and aggravations of gardening. In some cases, being able to look something up or have a backup set of seeds can have major impact on our success, which in some situations might mean the difference between thriving and barely scraping by.

Tracking Seeds & Results

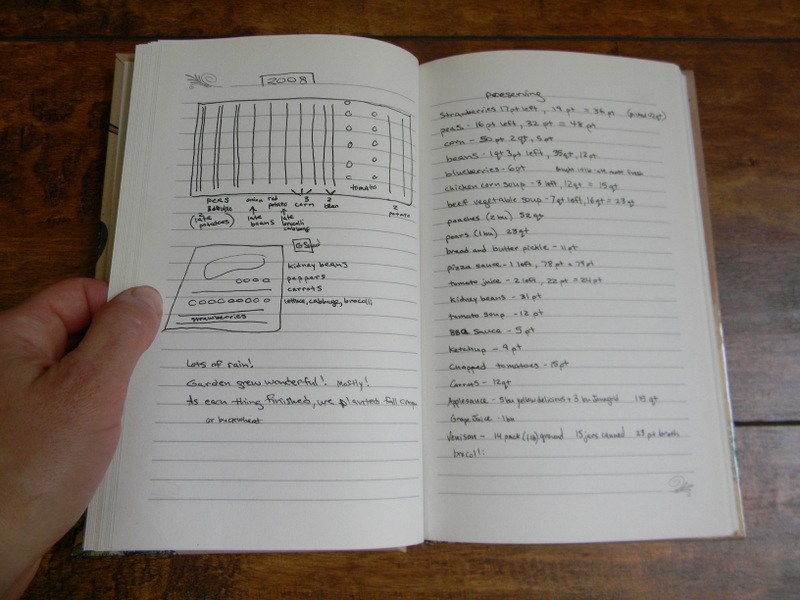

Notebooks are something most gardeners would benefit from. It’s not just for big growers and stock keepers. Consider a ledger your memory – because very rarely can our minds be relied on, especially if we have multiple companies’ offerings and multiple varieties of seeds.

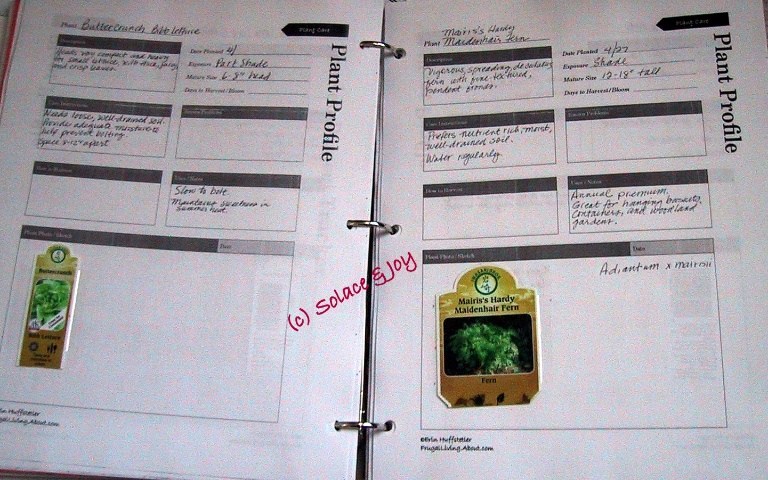

I like binders so that I can add a page for each successive year after I collect seeds, and so that I can add to my radish and squash/melon collection easily. Somebody with good backing-up procedures who aren’t worried about an EMP and who have a little solar charger for a tablet might be happier just making an Excel or Access chart. I know a guy who uses copier paper and the little report folders from green-sign Dollar Stores, keeping plant classes separated a little as he expands. A woman does the same, but hers are divided into ideal planting months for her climate. Lots of ways to tailor a seed book.

Regardless of what form our ledger is in, it’s there to tell us how seeds of certain cultivars and from certain companies respond to our soil, the climate and weather, and our culture practices (growing schemes).

Specifics to track in a binder

A basic seed book contains quick-reference information about our seeds, the information provided about them that tells us how to plant them and when. We do it for each variety by each supplier and each year, and ideally also have pages for our saved seeds from them, because all romaine lettuce and roma tomato seeds are not created equal.

Ideally, we also keep notes at least during key periods of the year. How many little green things popped up out of roughly how many seeds? How many grew up into strong plants? What fertilizers and treatments did we put out that might be affecting them? We also track climate conditions our little darlings survived, weekly or monthly – or during an extreme event. Hot and dry? Cool? Super wet season? Lots of wind?

Include notes about biotic conditions, too. How many bees are we seeing, and compared to previous years and bumper/bummer crop years? How many vegetarian creepy crawlies? Carnivorous buggaboos? Bats? Swallows? Crows? Was there a tragedy involving a border collie and a ball (or an idiot and a truck) that *possibly* affected a variety this year?

Include our feelings after we eat the produce (which is one place a dry-erase or chalkboard in a kitchen can be huge). Did we actually like the flavor of what we grew, or are we going to stand there with our eyes clenched closed trying to remember which one of those tomatoes/squashes was soft and kind of grainy and which was the most perfect thing we’ve ever put in our mouths?

The quick-list for a seed book:

- Seeds – cultivar, provider/manufacturer, days to harvest, spacing needs, seeding rate, planting dates, hot-cold sensitivity, drought/disease resistance

- Germination rate

- Plant health

- Weather

- Insects and animal activity

- Amendments and treatments used

- Yields (by cultivar and by location if micro-climates differ)

- Taste/texture and use preferences

Ideally in a format that can be quickly and easily accessed during planning and evaluation phases before and after each year’s crop seasons.

Ideally in a format that can be quickly and easily accessed during planning and evaluation phases before and after each year’s crop seasons.

A seed book might also contain generic information like:

- USDA growing zones

- Estimate charts of plants per person or household

- Average annual first and last frost dates

- Average annual rainfall

- Blank and previous-years’ planting charts/garden plans

It’s ideally in a format that can be quickly and easily accessed during planning and evaluation phases before and after each year’s crop seasons. Too many books and bookmarked sites, and it gets hard to have it all accessible on a kitchen table for easy consumption.

Using notes for planning & evaluation

A well-kept notebook can help us identify trends, and from that successful cultivars. It’s too easy to forget that something happened, and it’s too difficult to accurately judge productivity of peas if we’re not keeping track of harvest even just by using pint jars and baskets and colanders as our measure.

For kitchen garden and egg tracking, I find it easiest to stick a $2 Ollie’s dry erase board and a map pen by my kitchen door. That’s where stuff gets dropped, anyway. I can see it and note it immediately, while I suck down my ice water or sandwich, or when I move to dealing with it. I use a birdwatcher’s pocket notebook for large-scale crops going into drying bins, cellars, and curing sheds.

I find it easiest to stick a $2 Ollie’s dry erase board and a map pen by my kitchen door.

I find it easiest to stick a $2 Ollie’s dry erase board and a map pen by my kitchen door.

Then there are a few minutes then spent transferring the information to the specific seed/variety pages and to this year’s overall harvest pages later.

Seems like a lot of work?

It can be, and initial setup can take some time – a good winter or blazing-hot afternoon project. Once it becomes habit, it’s just adding tick marks on a chart of crops in rows and columns with the harvest size – individual fruit, pint, gallon, quarter-bushel – and a note that berries are getting nibbled on out there, then on with washing and sorting and processing.

Fast and easy enough, since I don’t want to waste more money on things that aren’t producing well, and I’d rather concentrate on things that we eat – especially if I’m hoping to make a dent in groceries off all this time and labor. Compared to weeding a conventional garden or suckering tomatoes, maintaining yield and field notes takes no time at all.

Our seed books also let us pre-plan our gardens without dragging all our seeds in and out of their nice, stable environment and exposing them to moisture and temperature fluctuation.

Once we have a notebook, we can also easily keep our printed/drawn garden and field plans – with notes right on them in some cases. That’s one more tool in our arsenal for future planning and identifying if and what went wrong.

If we don’t have previous years’ layouts and our yield notes, we don’t have the ability to study what went right and what went wrong, what plants followed each other and were near each other, or to act on it in the future. If we can’t identify which variety/varieties produced those bumper and bummer crops, we’re doomed to repeatedly plant the wrong one – or we might be looking for a condition that’s causing a change, rather than quickly identifying that it’s a particular seed type that’s varying plot to plot or year to year.

A good binder helps us in a lot of ways.

Segregated and Backup Seed Stocks

I separate seeds by type and season, especially if they’re being stored in a fridge or freezer. That way, when I’m frost sowing, early spring sowing, and summer sowing, I’m only exposing one set to condensation and moisture. Likewise, I separate my herbs and my longer-season carrots and rutabagas, because they’re only coming out twice, whereas my greens and radishes may come out to get planted and replanted 4-10 times a year. I don’t want to expose plants I don’t have to, and limiting their exposure to accidents can only be considered a good thing.

It’s also a time saver. I have multiple gallon Ziplocs of my “small crop” seeds and there are additional paper bags of beans, corn, some squashes, and peas. Sorting through individual packets in a box, larger bags, or bucket to grab the 5-20 packets I want for today can take longer than planting them.

Granted, inspiration can strike when a packet wings out at you, but for the most part, we want to get in and get done.

Backups are good. I also segregate by 2-3 year spans, and keep backups that are not coming out into the kitchen for pre-staging or out into the garden with me. That way grubby fingers don’t affect those backups, and if a cup of tea spills or there is a snafu involving slick, wet mud or a hose, I don’t expose every seed I have and end up needing to plant it all, now, or losing it because I can’t dry it effectively to re-store.

We backup data on our computers. We keep backups of important documents in our bags and vehicles and offsite. We keep and sometimes carry a backup firearm or an EDC kit. We have backup smoke and CO detectors. (Or we should – for all of them.) Some of us maintain studs or backup studs for livestock, or know where we can run in an emergency and secure one.

Seeds are no different. Because sometimes, seeds or whole plant strains end up wrecked.

Wrecked seeds are a bummer. Moisture or bugs get to them in storage, maybe they weren’t as dry as we thought when we bagged or jarred them and they mildewed, or they might have crossed, which we won’t know for six months or a year*.

(*The parent plant determines the shape of the fruit and the seeds inside. The pollen from a different squash variety can be hidden deep inside that seed, and it won’t show up at first. We might find out that we have weak plants early in a season, but we might not find out that we have only thin shells of “meat” or something more like a loufa or gourd until fruits grow and are harvested and cut open to consume – same deal with a lot of seeds, broccoli to corn to beans.)

We combat the chance of having seeds wrecked between harvest and planting, and the chance of a hybrid we don’t know about for a year, by keeping two or three sets of our seeds. One set we hope we’re planting out. One set we’re caching somewhere safe and holding onto for at least an extra year or two. That way if this year’s seed-saving doesn’t go so hot or if our spring planting reveals a problem with the previous autumn’s crop, we can revert back to a 2-3 year-old source that we have faith in.

Tracking and Separating Seeds

There are probably people more than capable of keeping track without a stock book or ledger for plants or livestock. Most of us can use the memory aid. Try it for a year or two, go simple with it, and if it’s not working for you, ditch it. I think a lot of gardeners will find that maintaining a seed book is helpful, even if they don’t go whole-hog with planning sheets and segregating seeds for efficiency. Maintaining backup stock to saved seeds is something I think everyone should be doing. If not for everything (I don’t backup everything) then for the best performers and severe-weather crops we count on.