Time is money. But so is prepping.

Hoping you had a great weekend. And that you are prepared for an even greater week.

First, let us remember why we gathered here today. To prep like no one has prepped before, right?

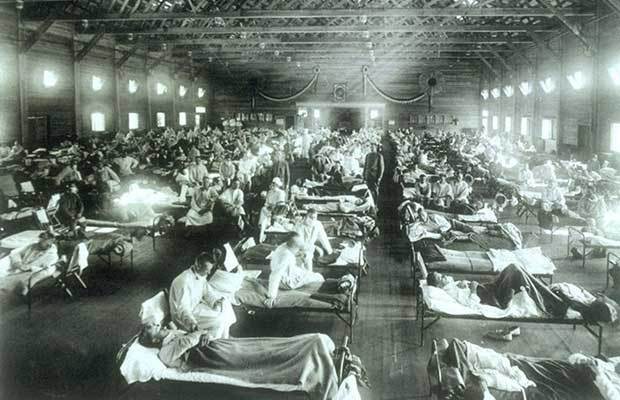

So what is prepping? The internet says it’s the practice of making active preparations for a possible catastrophic disaster or emergency, typically by stockpiling food, ammunition, and other supplies. So far so good. What the internet is not telling us is how to make these active preparations with the same money we struggle to make a living with.

Because all of our prepping efforts, besides a few DIY ideas, cost money.

So it’s time to talk money. And how do we make some extra for our prepping efforts.

Let’s go through some of the ways to achieving this goal, even if you might not find these ideas very attractive.

1. Sell some of the items you bought for your stockpile.

This is one of those ways of making money I think is a lot harder to do en-masse, but if you’re looking to make a few extra dollars on the side here and there, it’s an excellent way to go, especially if you’re particularly good at couponing, or getting items for free for your stockpile.

Have too much of a certain thing? I suggest bartering or trading these items, but you can also use these items to sell to friends and family and others who may want them as well. Cheaper for them to get them through you, and a little extra padding for your own wallet as well.

2. Learn a labor-related self-sufficiency skill and find work using that skill.

There are so many self-sufficiency skills you could teach yourself that would be beneficial for you to know as a prepper.

Some of these skills are more profitable to teach yourself than others. If you end up being interested in the right one, your knowledge could earn you a healthy side income if it’s something you’re interested in pursuing for money on the side. Eventually, your side gig can even replace your day job entirely, if that’s the direction you want to head in, or if you’d prefer – become a part or full-time gig during your retirement.

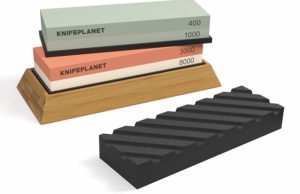

Examples of these self-sufficiency skills: carpentry and woodworking, electrical and plumbing, car repair. Knife sharpening is also a great one for transforming into a side business.

3. Learn a crafty or creative self-sufficiency skill and sell your creations.

Think this is ridiculous? It’s not! In this day and age where everybody and their mother loves looking up DIY posts, staring enviously at the result, and yet never doing anything of the sort themselves, there’s plenty to be made from a crafty self-sufficiency hobby that you picked up from your grandmother or originally learned to be more prepared.

Some examples of these types of self-sufficiency skills that translate into lovely creations that can be sold for a good sum on sites like Etsy: knitting, soap making, clothes making, leather working, and yet again – carpentry.

Even if you didn’t originally learn your skill to make money, doesn’t mean you can’t capitalize on your skill. You could even end up with a healthy small business on your hands in a few years time.

4. Sell hunted or fished meat to friends, family, and neighbors who are interested.

Meat you can grab at the grocery store just doesn’t taste the same as hunted meat – it’s not even half as good at the grocery store, at least not to me. There’s a quality about the taste of hunted meat that makes it worth so much more in my, and many other people’s, eyes. Same with fish you’ve fished yourself – rather than the farmed fish you often find at the grocery store.

If you have friends, family, neighbours, or acquaintances who don’t hunt and fish themselves, but love the taste of hunted and fished meat – you can stand to gain if they’re willing to pay you for what you’ve snagged in your spare time. With enough people interested, and going out often enough, you can really make a healthy side income doing this.

5. Sell excess fruits and veggies from your prepper garden to anyone interested.

Just the same as hunted and fished meat is infinitely more delicious to many than anything you can grab in a grocery store, home-grown organic fruits and vegetables are ridiculously better tasting when compared to their non-organic supermarket counterparts. I don’t think anyone in their right mind would deny this.

If you’ve already got a prepper garden started, you can try selling your fruits and veggies as is, or if you can or jar the fruits and vegetables yourself, can try selling them that way for extra as well. Make jams? Same as if you made homemade soaps – your handy DIY creations up for sale could result in you having a very healthy side income, or even a booming small business. All depends on what you want and how far you’d like to take things.

If you’re not comfortable selling these home-grown foods to friends, family, or neighbours, you can always try trading or bartering them for items they have that you need. It won’t help you make money prepping, but it sure will help you save money, since you save yourself the bill of paying for the items you traded for.

That’s it. But remember it’s only Monday. We’re just getting started.

Even if it doesn’t seem like it, this is Weed Week at Final Prepper. We will make sure we cover all the benefits of embracing this incredible new lucrative all American business, that not only helps its end users, but also the ones investing in it. Especially if they do it now.

Want to Save Money (for) Prepping? Make sure you read our articles this week.

Don’t forget to also send us your comments, ideas, or a story on your experience as a prepper so far.

It’s the only way for all of us to move forward.

God Bless,

Charles

It's time to talk money. And how do we make some extra for our prepping efforts. Let's go through some of the ways to achieving this goal.

A urban survival kit can give you the survival items you need to make it out of the city fast.

A urban survival kit can give you the survival items you need to make it out of the city fast.

In a disaster or crisis you could find yourself running for your life. Will you have the gear you need?

In a disaster or crisis you could find yourself running for your life. Will you have the gear you need?

Rush 24 by 5.11 Tactical

Rush 24 by 5.11 Tactical

After SHTF, you may have to be more careful when you are conducting business.

After SHTF, you may have to be more careful when you are conducting business.