Managed Livestock Breeding

Livestock keeping is one of the things that those interested in self-sufficiency regularly end up considering. There are factors involving breeding, especially, that can increase our success and let us custom-fit our livestock’s needs to our situations. While some aspects of controlled breeding may seem obvious, especially to experienced livestock keepers, other factors may not have been considered yet, or might lead to a spinoff idea (or a counter point). Those aspects also play a role in deciding which livestock we want – either species or “type” or specific breed.

There’s no one right or wrong way to do things, but applying managed breeding can be especially helpful on a small homestead and for those interested in sustainability. It’s something done on a large-scale by professionals, from meat cattle in Montana to rabbitries all over, and the factory farms that put eggs in the dairy coolers.

The Basics of Managing Breeding Seasons

Some animals are very like wild counterparts and have set breeding seasons. However, most of our domestic livestock are no longer locked into those cycles. That means we can apply the concept of controlled breeding or managed breeding – exposing females to studs at phased intervals that we choose to let us control every aspect thereafter.

The steps to controlled breeding are pretty simple. We work backwards through a lifespan or production cycle, looking at the conditions surrounding us and our animals, to include feed needs and forage, but with other considerations as well for varying life phases.

Seasonal availability of foods factors into wildlife breeding, and can play a part in managing our livestock as well.

We start with the yield we want, whether it’s milk, eggs or meat. Then we look at how long it takes to get there from birth.

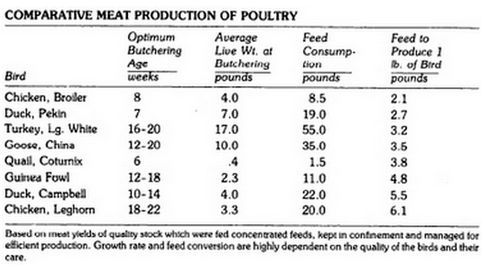

The time it takes varies, species to breed to specific location, and by the yield we intend to harvest.

There’s a big difference in the time it will take a sub-adult goat doe to start making us milk than the time it will take a doe purchased after a breeding is confirmed, and between that dairy yearling and wethers raised for meat.

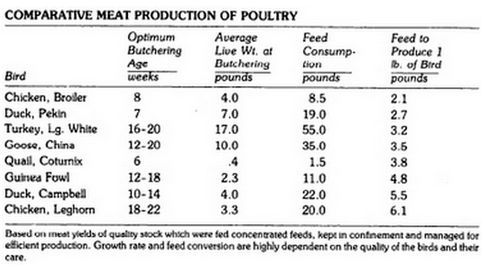

Whether for a secondary product (milk, eggs) or for meat, goats will get there faster than cattle; chickens faster than turkeys.

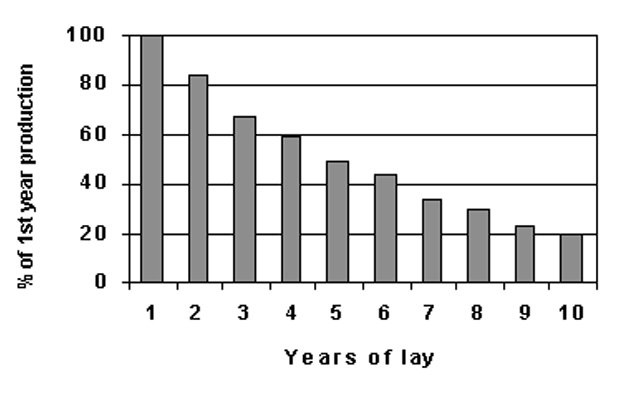

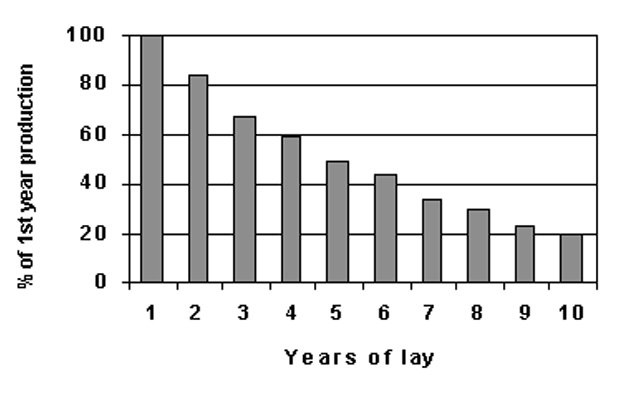

The amount of time that animal will continue producing also varies, both over a single completed cycle or annual cycles, and over lifetimes. We can manage breeding for replacements, inside a single-year cycle or on a multi-year cycle.

Feed quality also impacts production age, with forage-fed animals a little leaner and sometimes significantly slower to yield or with lower total yields. That can affect our management plans.

Chart: Laying hen production cycle by years of production

We might choose to plan kidding outside frigid & damp seasons so the young are at less risk; conversely, kids born in winter or early spring are closer to weaning as pasture becomes available for them, or we might plan on sheltered birthings when livestock is already penned and barned instead of caring for a pasture flock/herd as well as shed queens.

Different breeds within species reach their production sizes and ages in different times, too.

For example, meat goats can be milked, but they tend to produce a very high calorie, high fat milk in a very definite bell curve and for a shorter period of time than a dairy goat that lactates for 250-300 days. The dairy goat’s production will resemble a plateau for a portion of time, then taper off more gently. Knowing that, we might control buck exposure to meat does very differently.

Because of bagged feed and hay, and years of tinkering, we can control when they’re bred and thus condense our birthing and harvest seasons – or spread them out if that’s the goal.

Once we know the ages and plan the birth months, we count back through the gestation period to the ideal breeding season.

Factors in Controlled Breeding

Whether we’re old hats or just getting started, controlled breeding can help us. Counting backwards lets us consider what the pasture or barn looks like for birthing, our own schedules, other demands for our time such as busy garden and tree-crop harvests, predictable expenditures and income fluctuations, and even travel and vacations.

It lets us consider viable sperm counts in high summer heat compared to the rest of the year, body condition of the dams, and food availability of the type that our young – and their nursing mothers – need most in those cycles.

The two NRCS sheets from “Controlled Calving Seasons” here are really nice examples of factors to consider, as well as nice visual representations.

The first page looks at the practice of controlled breeding with pro-con breakdowns for Winter, Spring and Autumn calving. The second page uses a pie graph to visually represent the life stages and nutrient demands of female cattle for beef production.

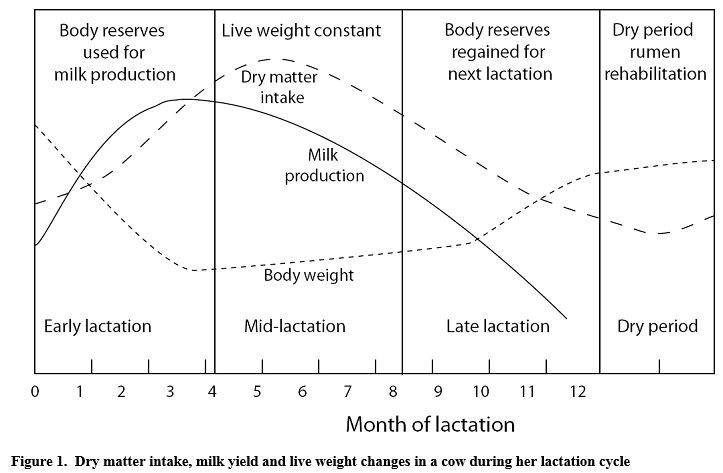

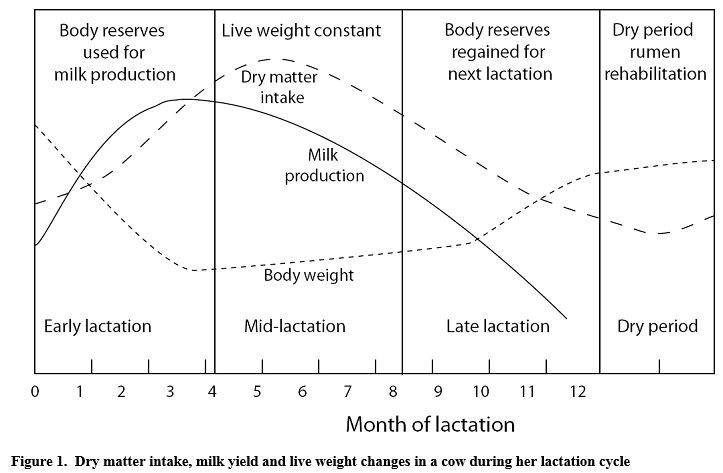

The time-frames differ, but most laying hens, meat breeding stock, and dairy goats have body stresses and peak production cycles similar to the dairy cattle shown here. The number of years they can repeat those cycles differs hugely, as do the amounts of feed, fencing, and human labor to reap the harvests.

Whether its meat or dairy, mammals or poultry, the basic tenets hold true. The goal is to help tailor breeding for times when livestock best fits our intended harvest goals and can be produced the most economically.

We can create the same breakdowns for when we allow hens to sit nests, taking into account the protein needs of the young as they grow as well as when we want a replacement nest of layers to get brooded so that we’re getting the most out of our feed.

We might also look at winter weather, or it might be pasture condition from typical summer droughts that most drive our timing. We might cycle the most and largest livestock around our water capabilities or freezer/canning capacity.

Available feed – and the nutrient content of feeds – and pasture conditions at different life stages should play a role in selecting breeding-birthing periods.

The general factors can be applied even if we don’t segregate breeding studs, by helping us choose what to do with each set of young.

By working through the factors such as in the NCIS sheets, we might discover that it’s far more economical to be culling one or another set, whether they’re intended for meat or to expand or replace dairy or egg producers.

We can earmark various litters or nests as keepers versus poussin or suckling harvests, fryers versus roasters, looking at when they’ll be producing or ready for harvest, and the inputs to get them there, and the “costs” on our pastures and breeding stock.

Example – Three Nests

Say we’re working toward sustainable laying flocks, and we know laying birds can produce in as little as 5 months (which is also a common meat harvest age for some breeds and species, especially free-range), but they might take as long as 8-9 months depending on species or breed, feed, the light amount and light quality, and the season they’re born.

Nest One – Laid & hatched in May

Feed: Whether it’s April showers-May flowers (and lots of bugs for the bug-hunting chicks, with relatively light growth they can easily get through) or bag feeds, they’re eating pretty good.

Production Month: It’s October before the first would start squatting and they might do their starter eggs before light really dims. Many breeds wouldn’t be ready to lay until December. A fair number won’t be laying their first eggs – or sizeable, yolked eggs – until they’re nearly a year old or older in spring due to winter’s light or feed.

Nest Two – laid and hatched in August

Feed: Some places still have flowers and bugs especially if we build bird-friendly feeder gardens/orchards and mulch walkways and pens so worms and critters will be in there decomposing the vegetation layers underneath, or maybe we’re restricted to worm bins and feed bags already; pastures tend to be tougher or becoming played over.

Production Month: It’s 5 months to January, 8 months to April, 9 months to May. In some climates, May might still be a little early on light needs, especially for new girls, but it’s close.

Note: I fed Nest Two 3-4 months less time than Nest One, with significant production for both starting the next spring (unaided). I might be better off harvesting Nest One for my freezer earlier in the year.

Nest Three – laid & hatched in October

Feed: Highly, highly variable by climate; most of U.S. and Canada are in grains and pumpkins and potatoes, tree seeds and fruits, with pastures thicker and taller and tougher or already munched down, and frosts already there to be a threat to young birds, or knocking on the door at birth. Then-maturing new layers are eating heavily during winter and spring’s regrowth months for a lot of places.

Production Month: It’s five months to March (which would be the earliest new layers x2 – both season and age by breed), 8-June, 9-July.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each.

Nest One gives me more eggs from the replacement flock the earliest in the next year, because the more mature hens are popping out in spring ready to be full-on laying stock even for late bloomers. Nest Two isn’t really far behind them, and if I bag feed exclusively or significantly, I saved a quarter of a year or so on them.

Nest Two will have lessened dependence on heat lamps early on, but climate will dictate whether they’re fully feathered for autumn-winter chill.

Nest Three is being fed for parts of autumn and the winter – when I have to feed all three nests anyway – and is still growing up during early spring and into early summer, but if I pasture, they get the bug-caterpillar season for some of their later-stage protein needs in addition to the potential of forage plots that include autumn grains and tree seeds-nuts that are full of good things for them.

From backyardchickens.com – The age of the birds entering winter corresponds not only to their size (flock integration) and feather cover (heat), but also the content and amount of feed they require during the stored-feed seasons.

Other Livestock & Aspects

That’s for laying hens. If they’re meat birds that I want to harvest at three to nine months by breed and type and feed system, I might run a smaller nest of all three, so there’s fresh waiting for chomping at intervals. Or, it might work better for me to raise a spring flock I can fatten all summer on less bagged feed, then freeze or can in autumn – leaving the seed-nut-grain forage for keepers and layers.

With dairy goats, I might control breeding so I stagger my does and births to get milk year-round. Or, maybe I plan kids for weaning and growing out for meat over summer pastures and so I can use the milk glut to fatten a pig or feed my dogs over summer.

I might choose to condensed breeding so that I can still travel over the holidays, or I might delay breeding so a neighbor isn’t babysitting during kiddings.

I might also time either mammals or fowl to account for the temperature, to lessen my reliance on heaters, and to allow for integration in winter after spring-summer separations. The joy of controlled breeding is that we decide whether it’s more or less convenient for us to provide heat and shelter and special feed for young and mothers separately during spring or summer, or to shelter them when the rest of the livestock is also penned and barned.

My separation and integration cycles might include my rooster or buck, for timing the next round(s) of raise-outs, for decreasing the number of snug houses I need, or to give my girls a winter break from the stud.

Existing coop systems might help me decide on breeding schedules, or instead I might design my coop systems to account for my intended production harvest – and thus controlled breeding in sets.

Infrastructure & Controlled Breeding

How I plan to raise something like poultry comes into play with infrastructure as well as timing the breeding. Controlled breeding goes down to the specific animals, even. For example, letting a broody hen nursemaid for me instead of incubating.

Is she senior enough to handle flock control or will I still need to separate each nest of young? Do I want to plan it so I have a separate flock of mothers with their nests? Does my flock have enough pasture and interests enough to keep them from harassing juniors in summer, but maybe not in winter?

I might plan my chicken lot with a primary coop or run, but smaller areas beside them or a fence-divided hen-house. That way I can let chickens sit and raise turkeys and ducks or their own young, but keep those hens better integrated, and have a “keeper clutch” that’s not quite up to body size for the main flock going in other attached sections to make transitioning them into the main flock a little less bloody.

Conversely, I might end up designing my breeding plan based upon existing infrastructure.

I might have every other input covered, but I just can’t afford to build adjoining chicken runs, to build a water system that fits my time budget for four pens of birds at different sizes plus the rooster, or to weatherproof or hen-proof a building to the level I’d need for a winter birth – not yet.

My intentions, needs and abilities matter, and affect or can be affected by the timing of my breeding, births, and harvest times.

Planned Parenthood – Critter Style

Managing breeding and birth and harvest periods can be big. With any luck, this article has had something for everyone, new or old hats. Hopefully the idea of separating studs from females is not entirely unheard of, but maybe some of the factors that play into our planning of those cycles introduced some aspect or consideration in that timing for everyone.

At base, maybe, everyone interested in livestock will at least crunch numbers and examine or reexamine their natural resources, and maybe even consider some of their infrastructure and inputs from a self-sufficiency aspect, then create a more efficient system.

Managed Livestock Breeding

Livestock keeping is one of the things that those interested in self-sufficiency regularly end up considering. There are factors involving breeding, especially, that can increase our success and

Running is something that I used to do fairly regularly. Actually, this is my 3rd 5K which I know is no Boston Marathon, but it’s enough for me to be able to get out and run 3 miles easily. I don’t need to do any more than that. When I first started running again I had been inactive for a pretty good while except the daily walks I mentioned so I wanted an app that would ramp me back up to a 5K. I found the

Running is something that I used to do fairly regularly. Actually, this is my 3rd 5K which I know is no Boston Marathon, but it’s enough for me to be able to get out and run 3 miles easily. I don’t need to do any more than that. When I first started running again I had been inactive for a pretty good while except the daily walks I mentioned so I wanted an app that would ramp me back up to a 5K. I found the  Pushups for me were a nightly routine that I would do more or less each night unless I forgot or was tired. My routine was anything but and I wanted something that could coach me to more push ups. I would crank out 20 or 30 and call it quits, but I found

Pushups for me were a nightly routine that I would do more or less each night unless I forgot or was tired. My routine was anything but and I wanted something that could coach me to more push ups. I would crank out 20 or 30 and call it quits, but I found  Situps was the next app and wouldn’t you know the makers of the Pushup app had a free app for sit-ups too!

Situps was the next app and wouldn’t you know the makers of the Pushup app had a free app for sit-ups too!  Another app I use to strengthen my core is one called

Another app I use to strengthen my core is one called  Lastly for the legs I have another app for squats made by the same people who brought you push ups and sit-ups above. Same concept and same execution.

Lastly for the legs I have another app for squats made by the same people who brought you push ups and sit-ups above. Same concept and same execution.