The Lowly Goat

I have been a prepper since just before Y2K. It has been an interesting journey that encompassed ‘peak oil prepping’, natural disaster prepping, EMP prepping and TEOTWASKI prepping. I’ve purchased all sorts of prepper gadgets and supplies, drooled over the Lehman’s catalog, ordered from a variety of dehydrated food company catalogs, improved my gardening and food preserving skills and changed a room in the house to a storage room instead of a dining room. But after all those years, all the prepper novels, the YouTube channels and lengthy discussions with like-minded friends, I have come to the conclusion that we just have to learn how to survive as our pre supermarket ancestors did. We need to have the skills necessary to survive long-term that were needed before electricity. Because once all our purchased stuff is used, we will have to know how to raise our food and fix things by hand.

There are thousands of articles on all things related to prepping written by people way smarter than I am. But I seldom find much on how to select and manage livestock after a collapse. My gardening skills are improving, I don’t know much about guns and my cooking and food preservation skills are a work in progress, but I have been around animals all my life. I’ve cared for livestock on my hobby farm for at least forty years so it only seems natural that I would decide to focus this article on animals from a prepper point of view.

One of the animals that I think will be a major player in sustainable living after the SHTF is the lowly goat. Goats can supply milk, meat, hides for clothing and be work or pack animals if needed. It’s time to look at what the goat has to offer and why I think it is better than a cow.

Both the cow and the goat provide the same products and many think the cow is going to be the perfect prepper milk and meat source. It is generally assumed that once the power goes off, dairy farmers will be giving, or bartering, their herds away because they won’t be able to milk them. I suspect this is true. So many preppers are planning on just grabbing one of those free, or bartered, cows and their milk and meat problems are solved. Short term, that will work for some and, worst-case scenarios, get others severely injured or killed. Let’s look at the cow and goat and explore why I think the cow is a bad idea and the goat is the perfect solution in most prepping situations.

The Backyard Goat: An Introductory Guide to Keeping and Enjoying Pet Goats, from Feeding and Housing to Making Your Own Cheese

Raising Goats: Goat Safety

The first thing to look at is handling. The average prepper doesn’t have a lot of experience handling animals…let alone milking a dairy animal. While we tend to see photos of contented cows in clean barns looking happy, cows are animals that weigh over a thousand pounds and very definitely have a mind of their own. If you don’t know what you are doing, the risk of injury when a cow swings her head around and accidentally drills you into a wall is very real. Don’t forget that she may not like your amateur milking efforts and show you her displeasure with a well-placed kick. Have you ever been run over by a cow that doesn’t want to go in the direction you want her to go in? Remember, doctors will be in short supply at best, so a broken arm that means a trip to the emergency ward today may mean something much worse in an STHF situation.

The milk goat, on the other hand, is usually under two hundred pounds. A cranky goat is much easier to handle than a moody cow and the likelihood of injury due to a kick is dramatically reduced. A doe (female goat) isn’t likely, although it is possible, to be able to swing her head around and send you sailing either. So from a safety point of view, especially for someone with little or no experience handling livestock, the goat wins hands down. Of course, if you have the handling experience, then a family cow might be something to consider. But keep in mind, if the collapse has happened, you will probably have inexperienced people staying with you. While the experienced people will do fine with a grumpy cow, how will the new displaced urban residents living at your bug out location do if they are assigned barn duties? Something to consider.

Since we are talking about safety, lets mention bulls and bucks….the boys! Breeding animals are not pets and in this case, both of these animals can be dangerous. Many an experienced farmer has been crushed by a bull after making one handling mistake. While a buck goat can be nasty, the chance of serious injury from a handling error is dramatically reduced just because of the difference in size.

Raising Goats: Goat Reproduction

Most people never give the breeding aspect of milk production a thought. Cows and goats have to be bred, and produce a baby, in order to produce milk (Some contradictory info on this later) . Farmers now days solve the problem of keeping a dangerous bull by, instead, using artificial insemination (AI). The AI guy comes to the farm with tanks of semen and breeds the cows. There is very little risk of injury. But after an EMP there will be no AI guy and the only way to get the goat or cow bred so she can keep producing milk, and offspring to raise for meat, will be to have a breeding bull or buck around. Life after a collapse of society is going to be jam-packed full of new and terrible dangers so it makes sense to choose the reduced risk of keeping goats that must be bred instead of cows.

Some of you will say “I can take my cow to the bull at the neighbor’s house” and that could be true in isolated cases. But two things should be considered. The average prepper isn’t going to keep a bull for breeding so finding that bull in your region will be difficult. Then you have to get your cow to the bull. You will be able to lead a goat through the woods. Depending on the woods themselves, leading a cow through the woods in order to avoid detection on a road is going to be a big challenge. Especially if Bossy isn’t interested in walking through the underbrush and jumping over fallen trees.

The reproductive cycle of the cow is continuous all year-long so you can breed her and have calves at any time. This means you can plan when you will have the biggest supply of milk. Goats have a breeding season, usually from mid-fall to about January. You have to plan carefully if you want a decent supply of milk for the entire year. This could be a disadvantage if you choose to have goats as your safe haven dairy animal but it isn’t an insurmountable problem.

Raising Goats: Housing your goats

The bigger the animal the more extensive the housing required to keep it healthy and happy. You can keep about six goats comfortably in the same space that you can keep one cow…. And the goats are not nearly as strong as a cow so your shed or barn doesn’t need to be as rugged for goats as it needs to be for a cow. The average prepper doesn’t have a barn but is likely to have a shed or garage that can be converted to shelter a dairy goat or two. Keeping goats in a small shed or garage is much more doable than housing a cow in one. Let’s not forget that a fifteen hundred pound bull is going to need a very stout barn and paddock area, as a bull on the loose is extremely dangerous. A two hundred fifty pound buck goat does not present the housing challenges of the bull for the prepper.

Obviously, if you have the space and shelter, then a cow isn’t going to present a housing problem…however, as a prepper who understands that security is important, you will probably appreciate an animal that you can easily hide. While not ideal, a goat can easily be housed in a cellar, on a porch or even in the home itself. I’m sure keeping a goat in the house is not something anyone would look forward to, but in some SHTF situations your animals are a critical part of your long-term survival and the ability to hide them from thieves, and wandering gangs, is an important consideration when deciding which dairy animal you will decide on. Cows will be MUCH more difficult to hide or even impossible. Keep in mind that livestock of all kinds will be far more valuable when food is scarce. In our modern world, livestock thieves are not common. But in a post-collapse world your livestock may be one of your most valuable resources. Your ability to protect and hide the livestock could be the difference between surviving and starving to death.

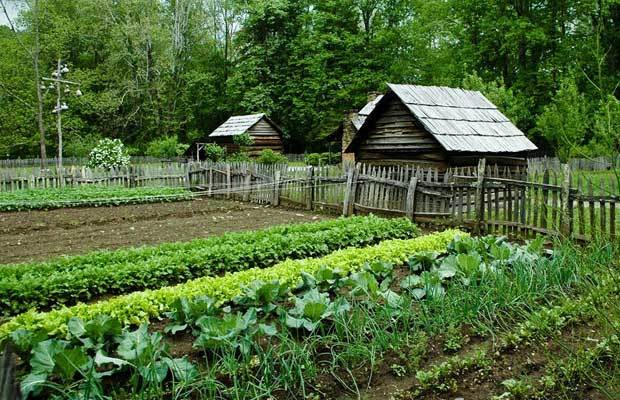

When discussing housing we can’t overlook pasture space. Cows are grazers and goats are browsers. That means that cows need good quality pasture to produce milk. Goats, on the other hand, browse (similar to deer)and are great at converting weeds to delicious milk. They don’t need large open areas of pasture. The downside is they love to eat trees and will kill any trees they have long-term access to as they strip off the bark of fully mature trees and eat the small branches of all trees. Eating an apple tree that is part of your long term survival plan isn’t a good thing but good fences and management will prevent that. Cows, because of their size, tend to destroy the ground in small pastures so it is important to have large grazing areas for cows. If you aren’t currently farming, and your dairy choice is the cow, you will need to have all the fencing on hand so you can put it up if TSHTF. You can tie a goat out and then move it as it trims everything within reach so a failure to have fencing prepositioned isn’t the disaster it could be if you plan on keeping a cow or two.

Another aspect of housing is feed storage. Keep in mind that in a complete collapse or an EMP, it is highly unlikely that you will not have access to baled hay. You will have to store loose hay, which takes up more space than baled. Do you have the space to put enough loose hay in a building to feed a cow for the winter, or is feeding a goat a more reasonable option when it comes to hay storage space available?

Bugging out with livestock

I’m sure this topic sounds out-of-place since we are talking about dairy animals….but it is very important to discuss in a worst-case scenario. The bottom line here is you can move a goat much easier and faster than you can move a cow. Without a stock trailer, you don’t have many options other than walking. The goat, on the other hand, can ride in the back seat of a car. If you are walking, they are usually easy to walk with and much easier to hide if you are on the road and need to jump into the woods to hide from other people you come across while traveling. You can even use a goat as a pack animal and there are pack harnesses available for purchase specifically for this purpose. The cow will slow you down and make it far more difficult to hide while the goat isn’t going to slow you down, is much easier to hide and can even carry some of the supplies you have decided to take with you when you bug out.

Raising Goats: Goat Milk

Before I get into choosing the goat I should probably address the issue of goat milk. Most people I talk to think that goat milk tastes terrible. Sometimes they are right, however, sometimes they are wrong and often there are good reasons for ‘goaty’ tasting milk.

When judging the taste of goat milk some things need to be considered. Remember that the whole milk you purchase at the store is bottled after some of the cream has been skimmed off. If you have access to raw cows milk try some and you will discover it tastes much different from the product you purchase at the store. Goat’s milk is naturally homogenized which means the cream doesn’t separate. So if you are used to drinking milk with reduced cream content, drinking goat’s milk that is rich in cream will either be a tasty treat or make you want to say “ugh!”

But the big complaint about goat milk is a goaty taste. The taste of goat milk is influenced by genetics so always try to sample the milk of a goat’s mother if you are buying a young goat. The food you feed your goat will also influence taste and that includes the types of plants growing in pastures. Undiagnosed illness or parasite infestation can influence taste so correct health management is important. Handling the milk after milking is critical in providing a quality product and chilling it quickly is the key to making sure you are properly handling the milk. Cow’s milk needs to be handled in the same way. And last, the condition and location of the milking area will contribute to the taste in the milk. Milk tends to absorb the odors in the air. Because of the unique characteristics of goat milk, it seems more prone to absorbing these odors. If there is a buck near the milk stand or you are milking in a garage with chemicals, the milk may absorb the odors produced by the buck or the chemicals. With all these factors influencing the quality of the milk to think about how you will store milk at your safe haven. Will you have refrigeration? If not, will you be able to use 3 to 4 quarts of goat milk a day or will you be able to find uses for 4 to 6 gallons of cow milk per day? It makes no sense to feed an animal to produce milk and then throw the milk away. For that reason alone, the goat may be the best option for a prepper.

The average goat is going to produce about three quarts of milk a day over the course of a ten-month lactation, with some producing less and others producing over a gallon a day. (Cows will produce three to six gallons a day). The amount of milk, for both the goat and the cow, is going to depend on the quality of feed, how long the animal has been milking, barn management and genetics. Remember, in an SHTF situation you probably won’t have access to good quality baled hay and grain purchased from the feed store. It is safe to assume that feed quality will go down and have a negative impact on production so choosing a goat that is an exceptional producer is important as that production will drop with the drop in feed quality.

Since one cow will produce a lot more milk in one day than one goat, you should look at your situation and decide how much milk you need at your hideaway. Do you have a small or large group of people? Are there children that will need milk daily? Do you have other animals to feed that could benefit from extra milk? Remember, you will have a much more difficult time preserving milk without electricity so planning ahead, as far as milk needs are concerned, is important. Will you be able to use four to six gallons of milk a day from a cow? Do you have children or adults who are lactose intolerant because many of these people can tolerate goat’s milk when they cannot tolerate cow’s milk?

Choosing the best goat for you

There are many different goat breeds but not all goats are the same. I am going to discuss the differences that are important from a prepper point of view. Some are dairy breeds (Alpine, Saanen, Toggenburg, Oberhosli, LaMancha, Golden Guernsey), some are meat producing breeds (Boer, Kiko, Kinder), some are dual-purpose (Nubian) and some are miniatures (Pygmy, Nigerian Dwarf). The Fainting Goat is a novelty that is listed as a meat breed but it claims to fame is a genetic disorder called myotonia congenital which causes the muscles to freeze for about ten seconds, rendering the goat prone and helpless when frightened. Then there are experiments which are crosses of two breeds and they include crosses of the normal size goats crossed with (usually) the Nigerian Dwarfs to produce a miniature dairy breed. The minis are cute and from a prepper standpoint much easier to feed, house and hide. But milk production is, on average, reduced to a minimum so it may only be an opinion for the small family or lone prepper.

Check out this article from “Mother Earth News” for an in-depth discussion of the breeds and their differences. Based on my experience with goats I do think that some of the milk production is exaggerated however you can see which breeds milk the best and which breeds have the most butterfat.

What about a mixed breed goat? Experimentals, the crossing of two purebreds, are often just as expensive as purebreds. Crosses are usually done to achieve a certain characteristic or because the goat breeder doesn’t have access to a purebred buck to match the doe. Experiments are great if they are a good cross that was designed to improve characteristics you are looking for, like increased milk production or better udder support. If the cross goes against what you want, such as reduced size of the goat or to produce more fainting goats that are helpless to predator attacks, you should stay away from the experimental. Mixes of unknown origin may be good if the seller can show you mom, dad, sisters, and cousins of the goat you want to purchase but in general, a mix of unknown origin is a big risk as you have a good chance of not getting what you hoped for.

The cost of a mix is usually the big reason for purchasing one but the old saying holds true here. “It costs the same amount of money to feed a good one as is does to feed a bad one.” In other words, if you feed a pound of grain to two milking does there is a good chance one of those goats will produce more from that pound of grain than the other. Genetics plays a big role in milk production and the only way to have a reasonably good chance of getting what you want is to get a goat with a known history.

Genetics also plays a role in the length of time a goat (or cow) will produce milk after giving birth. The dairy industry generally determines that an acceptable length of time for one lactation is ten months and then you dry off the cow or goat and wait for the next baby to be born to start the process again. But what happens if you don’t have a bull or a buck to breed the girls? While I cannot speak intelligently about how long a cow can milk if you keep milking her past that magic ten-month deadline, I can say that there are many factual accounts of goats being milked for years without stopping and without rebreeding. Milk production is not at the peak if you choose to just keep milking a doe but you at least are able to provide some milk if you can’t find a buck to breed her. If your bug out location or safe haven isn’t located in a place where you will easily have access to a buck, or if you can’t find a buck to purchase, you need to purchase your does wisely so you have the best chance possible of getting a doe that can keep milking long after you go past the ten-month cut off date. You need to find a doe or does with a proven history or genetic background of exceptional milk production and then hope that production will help her to continue producing for a year or more.

I am currently milking a ten-year-old LaMancha doe that has been milking for almost two years. She is giving me about a quart and a half daily. While that doesn’t seem like a lot, it is still more than my husband and I need and I am told her production will increase again in the spring.

A word about udders. In the world of dairy animals, the udder is the working part of the animal. It must have certain characteristics that will contribute to the cow or goat being able to produce milk over many years. Udders should be nice and tight against the body. An udder that isn’t supported correctly and hangs below the hock join in the leg is much more likely to be damaged if the animal runs. Well attached udders on a prepper dairy goat are critical to the health of the animal and its ability to bug out with you.

The purchase price is also a consideration if you are going to get started before disaster strikes. You have put a lot of money into your preps and purchasing livestock probably isn’t something you want to do. Unless your plan is the bartered farmer cow after the collapse, you will need to plan on spending $200-$500 for a good goat with a proven pedigree. You will be able to find goats MUCH cheaper but the chances of getting a good on at the cheaper prices is basically very low. If your survival depends in part on a dairy goat, you shouldn’t skimp on the quality of that goat.

Obviously, as I have mentioned above, you want to check out any known milk production records. However, there are other things to take into consideration as a prepper. Color may be important to you. Will a white goat such as the Saanen be more difficult to blend into the environment than a brown Toggenburg, LaMancha or Nubian? If you can’t effectively hide them inside a building or shed, then you will want goats that blend into the countryside.

The Nubian is known for their constant talking. Will that talking let neighbors know you have a nice milk and meat source just waiting to steal? Or doesn’t that matter? Speaking of talking, have you ever heard the bellowing of a cow half a mile away? There will be no hiding a talkative cow.

The Saanen is probably the biggest dairy goat and that can be either good or bad. Do you want to use them for pack animals too? In that case, you want big and rugged. Of course the bigger the goat the more food it will eat. Do you have the manpower to cut and haul food from the fields in large quantities? Keep in mind that goats eat about 4 pounds of hay a day vs a cow eating about 30 pounds per day. That is a lot of hay to harvest, haul to the barn and put in the barn.

Perhaps you want the kids to do the milking and be able to handle the goats? The LaMancha is often more ‘docile’ than the other breeds and might be a better choice for those who can’t handle the bigger framed goats.

Meat Too

Just a quick note about meat production. The goat often has more than one kid…sometimes as many as four. These kids, if not being added to the dairy herd, can either be used for barter or meat production. Cows usually have one calf and, when butchered, produce a lot more meat. While that sounds great, you have to remember that you have to preserve that meat and you may not have refrigeration. Butchering one goat means less problem processing than a steer. It also means that the other goats for meat can be kept alive till you need more meat instead of having to process and store your entire meat supply at the same time.

As I am sure you noticed, I think the goat is the perfect prepper milk supply. She will be safer to handle, easier to milk, easier to house, easier to hide and easier to feed than a cow. Unless your safe haven or compound will have a dozen or so people living there, the cow will produce so much milk in a day you will end up throwing it away. If you have to bug out, dragging two or three goats with you is relatively easy but transporting a cow or two if there are no automobiles or trucks running will be almost impossible and very dangerous as the cow will make you a big target for gangs. You won’t be able to move fast enough to hide her quickly.

After reading this article I suspect some of you will still say “A cow is the best prepper choice for me” and I’m sure that in some cases, a cow is a better option than a goat. But for the vast majority of preppers, who have never milked a dairy animal, and never cared for livestock before, the goat offers a solution that will fit nicely into the average prepper’s long-term food production needs.

The Lowly Goat

I have been a prepper since just before Y2K. It has been an interesting journey that encompassed ‘peak oil prepping’, natural disaster prepping, EMP prepping and TEOTWASKI prepping.

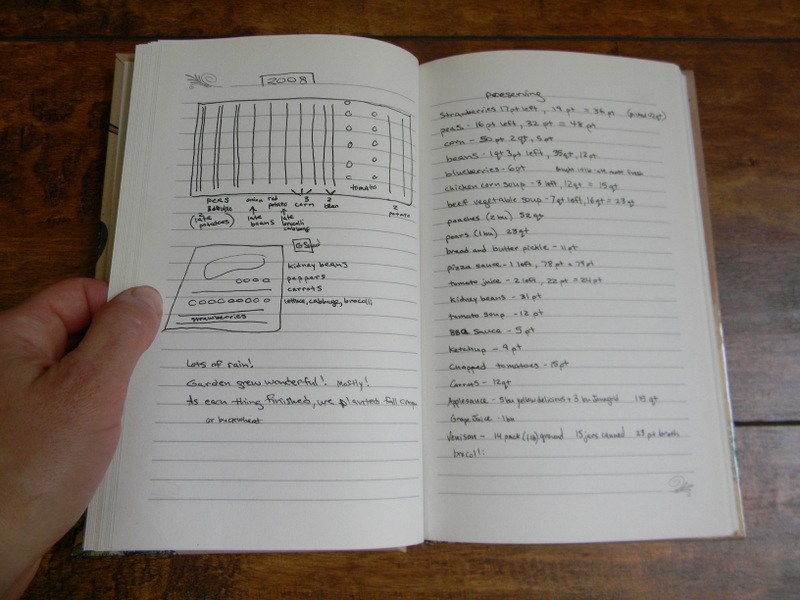

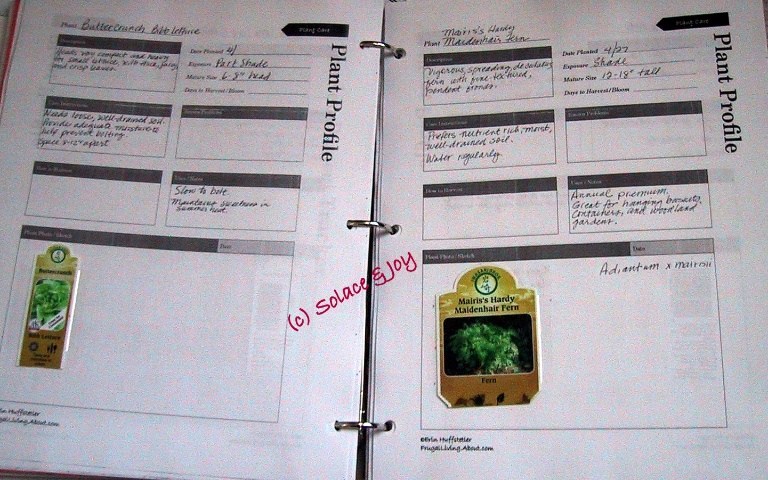

Ideally, we also keep notes at least during key periods of the year. How many little green things popped up out of roughly how many seeds?

Ideally, we also keep notes at least during key periods of the year. How many little green things popped up out of roughly how many seeds?

Ideally in a format that can be quickly and easily accessed during planning and evaluation phases before and after each year’s crop seasons.

Ideally in a format that can be quickly and easily accessed during planning and evaluation phases before and after each year’s crop seasons. I find it easiest to stick a $2 Ollie’s dry erase board and a map pen by my kitchen door.

I find it easiest to stick a $2 Ollie’s dry erase board and a map pen by my kitchen door.