In late 2009 my boss plunked a book with a hazard-yellow cover on my desk and said, “This might interest you.”

I didn’t know it then, but reading “The Long Emergency” by James Howard Kunstler would be the final push that changed the course of our lives. My husband, Darren, and I were already on the road to self-sufficiency but now felt utter urgency. Within a year, I quit my job. We sold all of our trinkets and trappings on eBay and bought a rustic homestead far from the city.

Written in 2005, the book details the numerous potential catastrophes facing humanity as we scrape the bottom of the oil barrel. None of them are pretty. Kunstler warns that humans are “sleepwalking into the future,” completely unaware we could be staring at our very demise while still buying electronic toys and microwavable lasagna.

Americans are a nation of overfed clowns, Kunstler said, who complacently tool around in SUVs, build unsustainable suburban McMansions and freak out if the power goes out for an hour. Many fail to fathom our fossil-fuel-driven industrialized lifestyle is merely temporary, just a blip in time.

Since Darren and I have practically all we need here, including an awesome deep-well hand pump for water, we seldom leave the county. Perhaps once a year, though, and since I still can, I’ll hop a Greyhound north to visit family. Last month as I wandered about in St. Paul, Minnesota, I was astonished by what Darren calls the “illusion of abundance.”

Every grocery store shelf was overflowing. I counted 12 different kinds of ketchup and massively long, wide rows of nothing but snacks. The mall was even more enlightening, as I haven’t been in one of those places for several years. I poked around in a dozen stores and never saw a thing I needed, or that anyone really needed. Mostly, the wares were just plain cute – knickknacks and paddy whacks.

At first glance, it all seems so plentiful. There is more than enough of everything to go around. But, do the math. How long would it take a half-million St. Paul inhabitants to consume every last morsel if no more groceries were to arrive magically by truck? As Kunstler points out, even farmers buy their food in supermarkets today.

We are in for a rough ride through uncharted territory.

Kunstler says it has been very hard for Americans — lost in dark raptures of nonstop infotainment, recreational shopping, and compulsive motoring — to make sense of the gathering forces that will fundamentally alter the terms of everyday life in our technological society.

“Most immediately we face the end of the cheap-fossil-fuel era,” Kunstler writes. “It is no exaggeration to state that reliable supplies of cheap oil and natural gas underlie everything we identify as the necessities of modern life — not to mention all of its comforts and luxuries: central heating, air conditioning, cars, airplanes, electric lights, inexpensive clothing, recorded music, movies, hip-replacement surgery, national defense — you name it.”

The few Americans who are even aware that there is a gathering global-energy predicament usually misunderstand that we don’t have to run out of oil to start having severe problems. We only have to slip over the all-time production peak and begin a slide down the arc of steady depletion.

Once the world’s leading oil producer, the United States passed its peak in 1970. Egypt’s oil production has been declining since 1986. A peak, of course, can only be discerned after it has passed. To intensify the issue, we must also realize that we have already extracted all the easy-to-get oil. What remains will inevitably cost more and be of poorer quality.

Because we have built our lives around nonrenewable cheap fossil fuels, giving it all up will not be easy for first- or third-world nations. Kunstler predicts economic, political and social changes on an epochal scale, and not terribly far into the future. Exactly when the chaos will erupt is hard to pin down, he says, because oil companies and nations haven’t exactly been upfront about oil reserves. That would be bad for business.

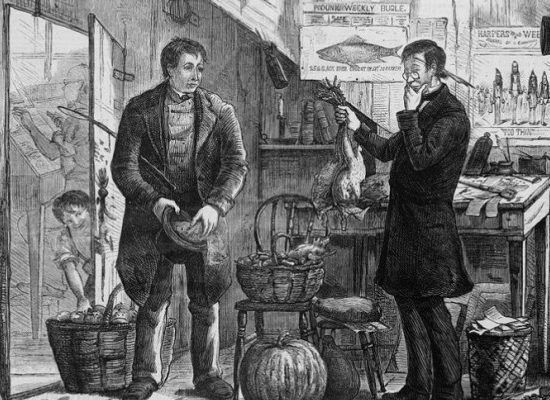

But, as Kunstler explains, as frightening as it is, we don’t have to do nothing. We must learn to trade locally again, feed ourselves and downscale everything from farming to schooling. It’s already happening small-scale around the country. Even in our little corner of Missouri, a group of food producers has formed a cooperative to sell their homegrown meat, eggs, milk, and garden produce.

A “simpler time” may be in our future whether we want it or not.

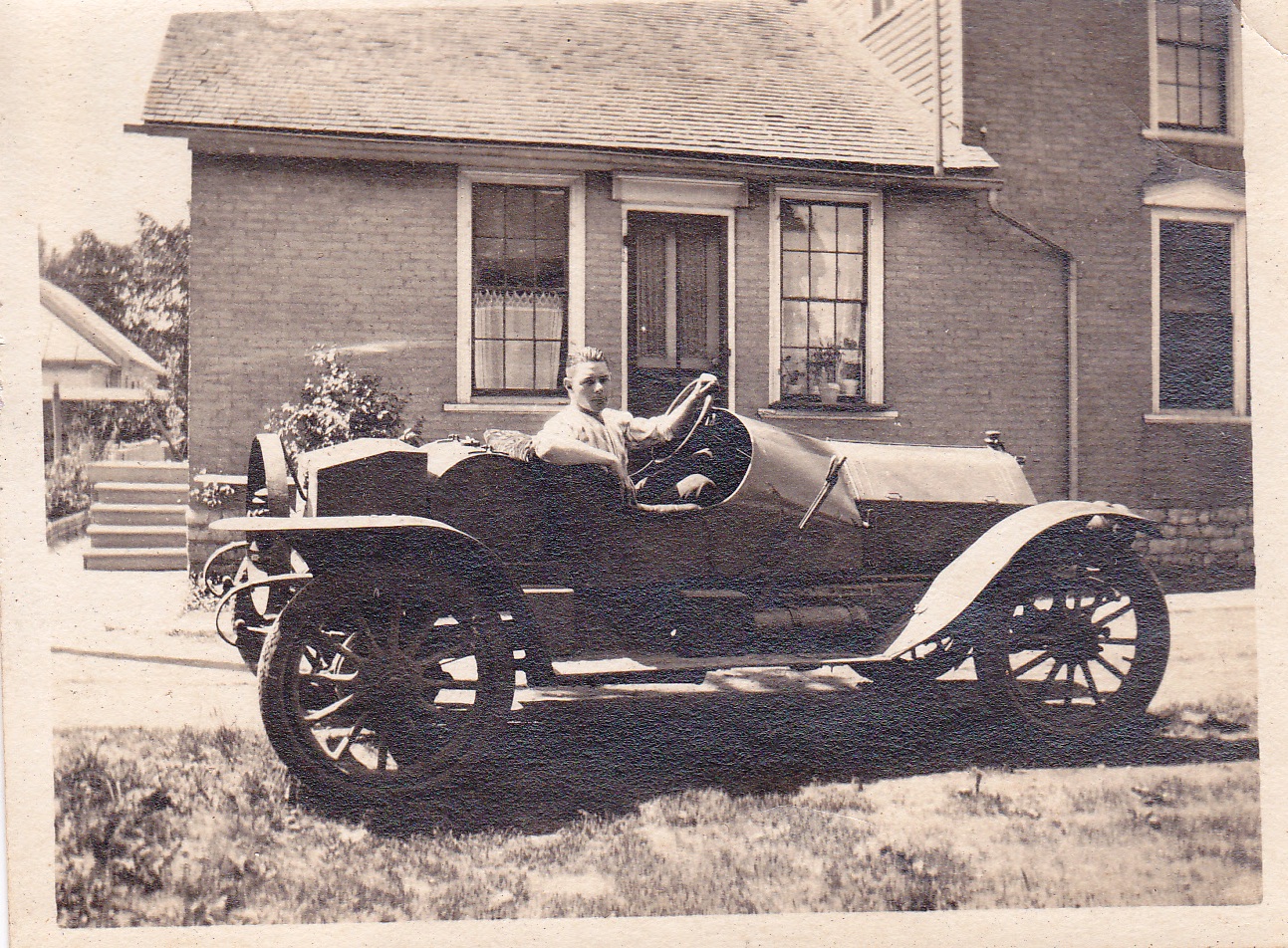

Not so long ago, since my grandparents were born, local was the lifestyle here in the Ozarks. A quick tour of the county back roads reveals numerous old country stores and schools now boarded up or converted to hay barns. Cars and store franchises killed those early settlements.

“We can be confident that the current set of arrangements will not endure,” Kunstler writes of our motor vehicle dependence. “Everyday life deeper in the twenty-first century will be as starkly different to people living today as the America of 1955 was different for someone who was a child before World War I. The automobile age as we have known it will be over.”

Kunstler says that if there is any positive side to the stark changes coming our way, it may be in the benefits of close communal relations, of having to really work intimately (and physically) with our neighbors, to be part of an enterprise that really matters.”