In small-space gardens, especially those with limited full sun in the first place, we sometimes feel like we have no choices. It doesn’t have to be that way and there are plenty of crop rotation solutions for even small spaces in your garden.

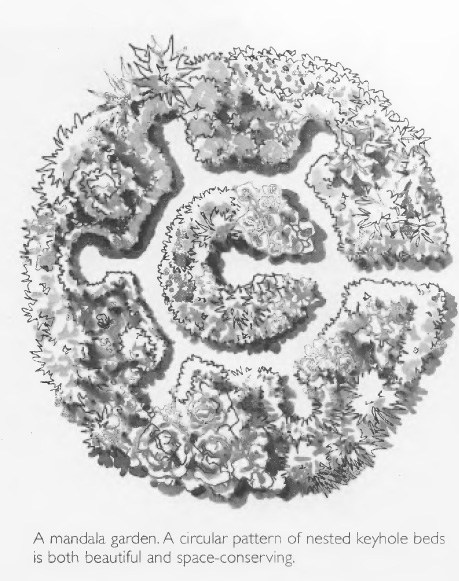

One of the most efficient systems for growing in small spaces are keyhole gardens. Sometimes they’re individuals, sometimes they’re nestled into a system that forms a mandala, and sometimes they’re surrounded by perennials and other beds, much like a pottager garden. The advantage to a keyhole garden is that it closes the gaps between beds and creates a lot more growing space compared to traditional rows, separated beds, and even those pretty pottagers. The downside, however, is that with limited space, sometimes we feel limited in not only what we can grow, but where we can put them. That puts a pretty serious damper on our crop rotations.

The “pizza” garden rotation plan that was mentioned in the first crop rotation article is scaleable. The author lists two – an eighty-foot and a forty-foot diameter that results in whopping 1K-4K square feet of growing space. That could easily be reduced further, but there are some additional factors – like shading – that crop up as we work with small spaces.

Do the rotations matter as much in such small beds?

Because small beds are typically going to be more diverse, with more plants making close contact with each other, we gain “edge” diversity. Just like we find a ton of game and foragable foods at the edges and margins – where rivers slow, where fields meet woods, where the forest is broken by streams – having multiple types of plants in a space creates lots of niche habitat for the microbes.

That soil biology does even better because we typically don’t till our E-shaped and C-shaped raised beds to the same degree we do in-ground and straight beds. The intact soil biology matters. It’s the microbes that let legumes produce excess nitrogen to leave behind, and the microbes that cycle compost into available nutrients. If we practice good culture like seasonal or year-round mulching that prevents compaction, we don’t have to restart the process every spring.

Healthy soil makes healthy plants. Healthy plants shrug off pests and diseases better.

Even so, the individual plots do start harboring sweet spots for diseases and pests. I once read an author who pointed out that if a cabbage beetle larvae wakes up and finds itself two feet from a patch of kale, it’s just as happy as if you’d planted beets right on top of him again. Same goes for some common corn and tomato-potato pests, and a whole lot of pests that like to eat our brassicas (collards, beets, broccoli). We can restrict ourselves to the brassicas like mustard and upland cress that those pests don’t like, or we can figure out ways to rotate our garden space, put disruptive crops and companions between them, and still have turnips year to year, even with shade-casting plants.

Big plants in small spaces – Why bother?

Small space growers have been turning patios, porches, and decks into bumper crops of veggies for years. Cuba’s oil crisis makes an excellent study of the impact urban growers can have. It’s not just the cut-and-come-again herbs and greens, or things that give a lot of bang for the buck even with just one or two plants, like summer squash and tomatoes. We now have OP sweet corn and popcorn bantams that produce in 65-75 days and are happy growing in a washtub, storage tote, or filing cabinet drawer.

Will those make an enormous impact on today’s diet? Not so much. But they do allow a small-space grower to keep a fresh seed supply going, learn exactly what pests they’re fighting, and be better prepared, even if there’s still a big learning curve after a disaster when they jump into currently lawn-covered dirt.

Remember, not all crises are created equal. Cuba and Argentina are excellent examples where there was a for-real, shopping-stoppage disaster without a complete breakdown of life as we all know it. The Great Depression is another. Victory Gardens here and in the U.K., and the British Ministry of Agriculture’s response to World War II are other excellent examples.

Today’s city dweller or suburbanite may very well be learning ahead of time, so that when it becomes not only acceptable but encouraged to plant in the space between sidewalks and parking lots, they’re ready. They may also be trying to save money for that perfect retreat location, but be practicing now so they recognize pests and nutrient and water problems right away when they do have a big space.

A small-space grower might also be working 50-60 hour work weeks, making time for family, and be learning other skills to benefit their 10-20-120 acres. They can’t handle 500-1K-5K square feet of veggies and staples right now. When the time comes, they will bust out their cultivators and be better prepared since they have an established line of crop seeds – propagated for years, proven stock that works well with their exact climate.

There are lots of reasons to be growing in a small space and to be growing no matter where we live. However, those small spaces do sometimes present some challenges, especially with crop rotation.

Small-bed challenge – tall plants & big plants

When we lay out our gardens, the goal is generally to keep tall plants from shading small plants. This means the back-north of our bed is somewhat limited to corn and tomatoes most of the time.

Corn and tomatoes do not give us a great many options in our crop rotations.

It would also be pretty sweet if we didn’t have to devote quite as much space to sweet potatoes and zucchini to keep them from choking-out everything in their path.

Happily, these two problems go hand-in-hand with a solution: we avail ourselves of trellises.

We could make trellies and cutesy wigwams from Lowes material. Or we can start looking at other people’s trash in a new light, buy ourselves some garden-friendly paint, and find a child (or fake one, I don’t care) to cover up our seat-removed chairs, DVD racks, deconstructed dog kennels, and mattress box springs with thumbprint butterflies and handprint flowers so our spouses and neighbors have to grumble a little more quietly or find themselves accused of being both environment-killing disposable-world dirtbags and heartless child haters.

So how do we apply our neighbor/spouse-dodging trellie? We add to our list of “tall” plants for the back of the bed.

Now we have corn, tomatoes, cukes and summer squashes that we’re going to cut small, eggplant and autumn squashes and melons that we can suspend in mesh or pantyhose or t-shirts, Malabar spinach, any pole or vining bean that will happily climb, and peas. We can trellis sweet potatoes, too, although we have to dedicate weekly time to encouraging it up instead of out (zig-zagging line around it).

Since peas, some tomatoes, our big basil plants, and our summer squashes are either a little shorter or a little looser, we can even pack them in front of some of our more shade-tolerant varieties like Malabar and things like Chinese yardlong beans that grow up-up before they bush out, and won’t be affected by shade at the 3-4’ level. We can also stick looser-branching things we can train wide like cucumbers up on a lower trellis in front of our corn once the corn is well established.

If our spouses won’t bury us in the bed, we can make canted pot towers, stacked bucket towers, or soda bottle towers for strawberries, lettuces, spinach, herbs, onions, chickweed, strawberry spinach, and edible/companion flowers to intersperse as our “tall” rotation. Some of them aren’t going to do so hot behind bushy corn or tomatoes, but pruned tomatoes and the lower or looser squashes will be fine.

Growing vertically doesn’t only expand the rotation options by giving us more tall plants for our northern and dawn-or-dusk sections, it can actually increase the total yield of our small space. We need to compost and drop tea bags and coffee right on the surface through the season (you can get free coffee grounds at Starbucks and McD’s), and we will need to water more. Still, we can further decrease our grocery bills and increase our seed stocks doing so.

And we don’t have to spend a fortune or eons doing it.

Small space rotation challenge – succession planting

One of the other key issues with small plots is succession planting. We might still stagger planting for staggered harvests, but the space for that is a little more limited. However, big or small, we like to rush right out there and get our nails dirty again at the end of winter. When we’re dining off limp dehydrated and canned foods and spoonable wheat, corn, rice and beans, the crunch of romaine, Napa and radishes and the roast-and-stab appeal of a 40-60 day turnip is going to be even bigger.

The problem? Three of those four examples – and other cool crops like kale and beets – are brassicas. Brassicas have two soil-borne diseases, soil-hatching leaf-eating larvae, and some aerial threats that inherit the memory of where the buffet is laid out. If we’re not rotating our brassicas, we start losing them to pests and disease.

What’s not a brassica? Spinach and chard, a lot of the lettuces, radicchio – so there are some options.

We can congestion plant marigolds and nasturtiums to help combat brassica pests. That’s not a marigold between every other plant. That’s a blanket of marigolds that we dot with cabbages. The marigolds work not even so much for this year, but more like legumes and nitrogen-fixation – they leave behind things that benefit other plants, in this case, limiting soil pests for future brassicas.

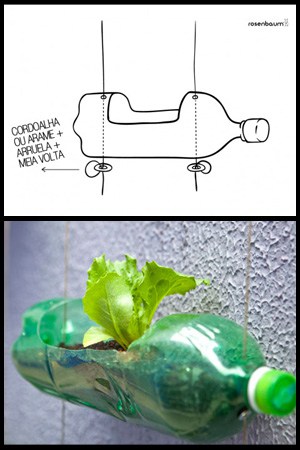

Our soda-bottle towers can help us here, too. We can also make ladders of bottles, bread pans, or storage totes to grow larger cabbages, root brassicas, and kale in, then compost that soil, microwave or bake that soil, or rotate that soil to herbs and flowers the next year to prevent a beetle’s sauerkraut-killing children from just leaping out and eating our stuff again.

That leaves us with most things like broccoli and Brussel sprouts that truly take up a footprint in our beds. And since we now have a wealth of things that can be about the same height like peas, beans, squash, and sweet potatoes that we can rotate with them, that’s just not a very big deal anymore.

Legumes

Peas and beans will share some pests, too, but usually, in tight beds full of diversity, that stops being as much of a problem. With rich soil, we can throw away the companion planting “bad buds” myth of peas and onions, which means our alliums help fight off those pests along with our marigolds, alyssum, and nasturtium.

So, again, the high diversity in our small spaces, keyhole, mandala, or E-shaped beds helps us.

Rotations in miniature

With all the options available to us as Craigslist hunters and internet gatherers, even small space growers can be very successful, not only in yield but in the rotation systems that build and protect soil, and make future yields just as successful. We can increase our options by including edible and medicinal annual flowers and herbs. We can further increase our rotation options with tiered containers of perennials like strawberry, thyme, and chives — which we can pack into the “keyhole” slots or the walkways between raised beds and cover for the winter.

We’ll be more successful if we adopt rotation systems, regardless of our scale. We can save money on soil and plant treatments and sometimes on our fertilizers by doing so, allowing increases in budgets for other preparedness goals. We can limit some of the amendments and treatments we have to make room to stockpile.

We might find some joy in a garden that’s not making us pull our hair out with a new problem every week. Importantly, we’ll be more familiar with crop rotation systems should a time arise that we must increase our food production.

When we look at things differently and don’t handcuff ourselves because of our space, bodies, budgets or time when we start seeing challenge-solution situations instead of problems, we set ourselves up for success – not only in gardening efficiently and effectively but in every aspect of our lives.