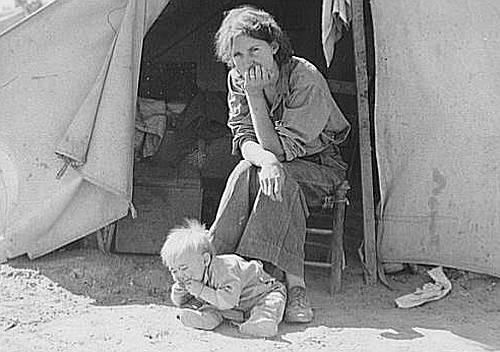

Editors Note: I don’t know what the future holds, but history has a funny way of repeating itself. I would be lying if I said that I have an optimistic outlook for our near term future. For a myriad of reasons, myself and others like me are preparing for a time when the stupid antics of a messed up 20 year old starlet at an award show aren’t worthy of news attention, because the world will really have more important things to worry about. My fear is going through something worse than our grandparents did in the great depression. What I am concerned about are things like my family’s safety, how I will feed them and take care of them. I wonder about what their lives will be like and if we will live to see them grow old. These are normal things for a parent, but we can easily forget just how difficult life can be and how it can catch up to us when we aren’t looking.

I came across this story below. It is mostly photos with a few poignant memories taken from people who actually lived through the depression and had some of the difficulties in life that I fear. I wanted to share this with you because I want to make sure I remember that it can all come crashing down so easily and not to take the time and our lives for granted. This is also a chance to reflect on generosity and how you may be faced with the same opportunity the people in this story had of giving some measure of comfort to a person who didn’t have anything else.

By Errol Lincoln Uys: excerpted from Riding the Rails: Teenagers on the Move During the Great Depression

“When Did You Boys Last Eat?”

In October 1929, Oklahoman Edgar Bledsoe believed a newsboy’s cry of “Stock Market Collapse” referred to a disaster at an Ardmore cattle auction barn. By 1932, Bledsoe had been riding the rails for two years picking cotton and doing menial work that rarely provided a living for the 18-year-old and two cousins. That summer the trio rode a freight to Comanche, Oklahoma heading back to his cousins’ home on a drilled-out oil field. They had to walk the last 13 miles through the woods.

“We ran across a log cabin deep in the blackjack oaks. It had a well in the backyard with a rope and a pulley. A man who must have been close to ninety years came out of the cabin. We asked if we could have a bucket of water,” Bledsoe recalled.

“‘When did you boys last eat?’ the man asked.

“When we told him, he told his wife to bring us food.

“She set out a gallon crock that was half full of milk, a pone of cornbread and a bucket of sorghum molasses. The milk was beginning to turn sour — ‘blinky’ we called it — and the molasses was full of tiny ants. We were hungry beyond being picky and we lit on the food. I still remember we couldn’t fault the old lady’s cornbread.”

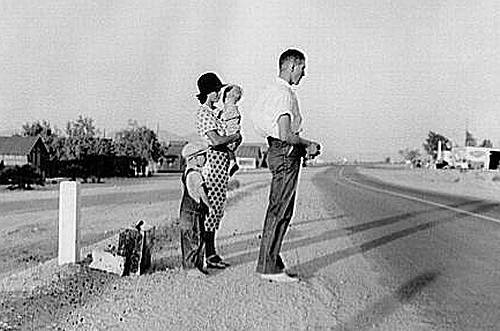

At the height of the Great Depression, a quarter of a million teenagers joined the ranks of the army of migratory idle roaming across America riding freight trains or hitchhiking. — In 1933, when the economy hit rock bottom, about 9,000 banks failed, $2.5 billion in deposits was lost, unemployment soared to nearly 13 million or about one in four of the labor force. Not since the civil war had the American nation stared so deeply into the abyss.

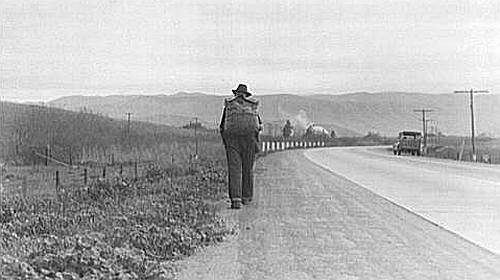

Some youths ran from home believing they were burdens on their families; some fled, broken by the shame of unemployment and poverty; others left eager for what seemed to be a great adventure. Romantic ideas of life on the road vanished when a young hobo felt the first pangs of hunger.

The majority of homeowners and shopkeepers were sympathetic toward the hard luck kids. Sixty years later, the simplest acts of kindness were remembered by those who’d been half-starved and utterly dejected when they knocked at a stranger’s door. Other kids, too, recalled seeing their mothers and father help hobos who came to ask for food. It was a lesson in giving that was never forgotten.

“Put Your Pride in Your Pocket.”

The roving horde was constantly hungry living for days on stale buns and bread or “toppings” and frequently going without food at all. Recalled Clifford St. Martin, who was on the bum from 1931 to 1938: “When I woke in the morning I worried about something to eat. After breakfast I worried about where to go. In the afternoon, I’d more worry about getting food. When it started to get dark, it was time to worry about a place to sleep.”

On Peter Pultorak’s second day on the road in 1931, he met an old tramp and asked him how to get by without money. “Put your pride in your pocket, your hat in your hand and tell them like it is,” his mentor advised. The lesson served Pultorak well riding the rails for the next eight years from his Detroit home to the blueberry harvests in northern Michigan.

|

|

Dirty and hungry and far from family and friends, numerous acts of kindness buoyed the young migrants. William Aldridge retained a lifelong memory of a pretty girl who opened her door to him. “I asked for a glass of water which she brought me,” Aldridge recalls simply. In southern California as he walked beside the tracks, a brakeman tossed Aldridge a quarter. “Go get yourself a meal, kid,’ the man said.

“The Buzz Saw of Life”

Paul Booker was 16 when he decided to go on the road in June 1931. He hitchhiked and rode freight trains from Bedford, Indiana south to Texas and Arizona and then back north to Seattle. Riding from San Francisco to Seattle at night, he fell between two box cars when the train lurched. Only because they were moving slowly could he grab a steel bar and pull himself back up. In Texas, he was shot at by railroad bull Texas Slim as he fled the Longview yards; in the northern states, vigilantes threatened to shoot him if he tried to climb off a train.

“I thought I was tough but changed my mind finding myself suddenly thrust into the buzz saw of life,” said Booker. “I arrived in Milwaukee weak from hunger, my lips in scabs from sunburn and thirst. My only goal was to get home as soon as possible.” A fast mail train was getting ready to pull out of Milwaukee’s Union Station. It carried no passengers except one: Booker grabbed the back of the engine and climbed onto the water tank. In a short time, he was in Chicago.

“An angel in the form of an 80-year-old woman touched my hand in downtown Chicago. She asked if I needed help. When I told her my story she pressed a dollar bill in my hand. ‘God bless you, son,’ she said.

“Good Place for A Handout”

The young hobos never forgot those who reached out to them in their time of need. For their benefactors, too, the ragged bands who knocked at their doors were remembered, especially by the boys and girls of the house. Many were deeply touched by seeing their parents’ compassion toward total strangers.

In the 1930s, Albert Tackis’s family lived in the small West Virginia town of Colliers, where their house backed onto the Burgettstown Grade. Two-engined freight trains stopped at a water tank behind the house before starting the 30-mile haul to Burgettstown. In summer, Albert would see 60 or 70 hobos climb off the cars to stretch their legs, every train delivering as many as eight hobos who came to the Tackis home to ask for food.

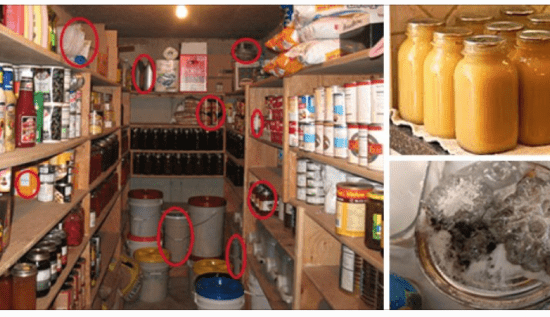

“We were five people in our family: mother, father, grandpap, my sister and me. Grandpap grew all our fruit and vegetables in his garden. In season, mother canned vegetables and made jellies. Every week, she baked 21 loaves of bread.

“When grandpap saw the hobos coming to our house, he alerted mother who would start making egg sandwiches and packing bags with carrots, tomatoes, apples and peaches. Grandpap always had something for the hobos to do. There would be wood to chop, cans to pick bugs and insects in his garden, buckets to fetch water from a spring. The hobos worked for about 20 minutes and then hopped back on the train with a good meal in hand.”

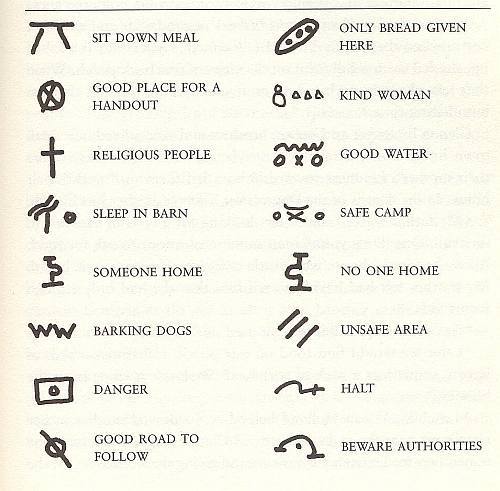

At Cottonwood, Idaho, William Loft — a local dentist’s son — would watch the freight trains pull in with tired hobos riding on the top “sitting with their heads slumped down and looking more like sacks of grain.” One day William saw one of the men put a mark on their fence. He ran out and asked why he did this. The hobo explained: “Son, when you’re starving and on your last legs, this means there’s a hot meal and friendly people you can trust.”

The mark on the Loft’s fence was one of many signs hobos traditionally used to alert each other to houses where they could get a handout, what approach might work best, and what houses were best avoided.

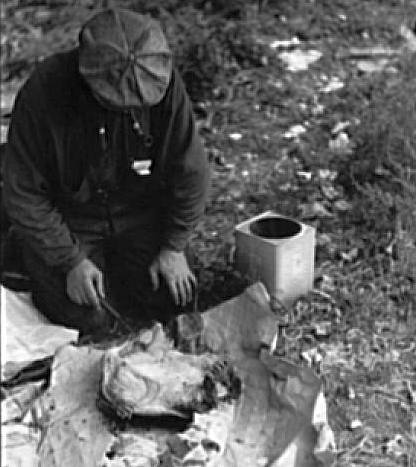

“In the Jungle”

The one place where the young hobo was assured a welcome was the “jungle,” as the hobo camps were called. These were generally not far from the tracks, some nothing more than a clearing for a camp fire, some well-established sites overseen by old jungle buzzards who set up home there.

Between stops at transient camps, Gene Wadsworth dropped into hobo jungles. He found permanent denizens of the camps living in shacks made of flattened tin cans, boards, railroad ties, anything that could be scavenged to build a shelter.

When a freight train rolled by and hobos started arriving, the old buzzard would issue instructions: “Hey, you, Whitey, go up to the meat market and ask for scraps.” — “Red, you go get carrots.” — “You, skinny, go find spuds.”

“I’ve seen stuff go into a stew pot that I wouldn’t feed to a hog,” recalled Wadsworth. “We’d take a tin can and the old ‘bo would fill it. If he liked your looks, he’d dip down deeper for meat and vegetables; others got mostly soup.”

Fredrick Watson knew the Pocatello, Idaho jungle from a different perspective. His father worked in the Union Pacific yards at Pocatello. Watson recalled that the jungle was on the west side of town near the Portneuf River.

“There was always a population of 100 to 150 people, including entire families with kids. They weren’t bums but good citizens who were flat out of work and trying to get by.”

Watson and his young friends would go to the jungle and eat lunch or dinner with the hobos. “We would take our share, mostly coffee that we purloined from our homes. Mom and Dad probably knew about it but didn’t say anything.”

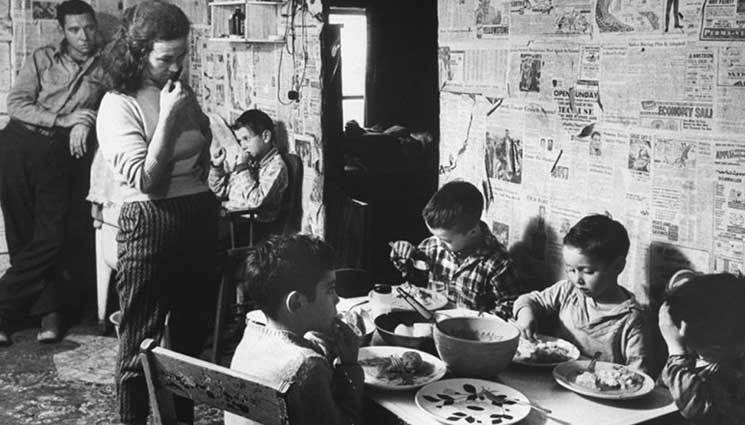

Ann Walko was deeply moved by her mother’s compassion for the downtrodden who came to their home at Wall, Pennsylvania where freight trains were broken up and re-routed.

“One day a man came to our door asking for food. Mother invited him in but he stood in silence for a moment.

“‘I have a family with me,’ he said.

“Mother said she would feed them too. He brought his wife and three children. They still refused to come inside so mother spread two rugs on the ground for them. They ate her home-made bread and baked beans and couldn’t thank us enough. In a way what a beautiful time it was.”

©2009 Errol Lincoln Uys

excerpted from: Riding the Rails: Teenagers on the Move During the Great Depression

Great Depression era photographs: Part of Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection/ Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division Washington, DC 20540. See individual image credits.