Planning Your Homestead Orchard: Benefits of Dwarf Trees

Dwarf Trees – When Less is More

We spend a lot of time looking at annual crops and gardens, but perennials have their places. When it comes to fruit trees, we have many options in sizes. There’s little more majestic than a full-sized cherry tree, and not much will match a standard apple for yield. However, there are a lot of times when we’d be equally or better served with a smaller tree, and lots reasons to consider dwarf trees or semi-dwarf instead of a standard, even when there aren’t space constraints that affect the ability to get pollination partners. I’m starting with a primer on size and expected yields by size and species, then hitting considerations such as maintenance, resiliency, harvest size, and more.

Tree Sizes

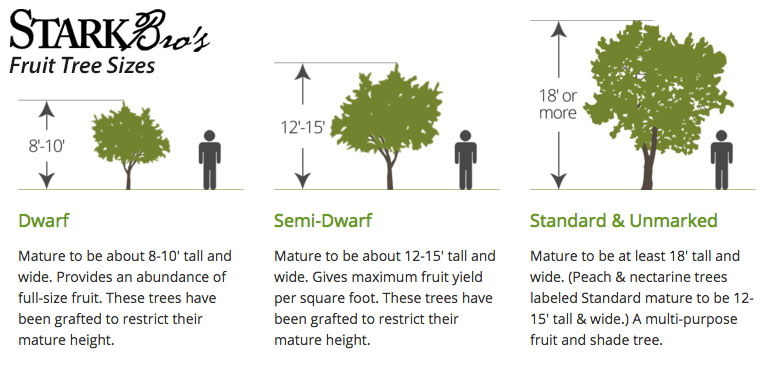

There are some generally accepted sizes for dwarf, semi-dwarf, and standard-sized fruit trees.

A lot of fruit trees have about the same spread (circular footprint) as they do height. Dwarfs are usually 8-12’ (also regularly seen as 8-10’), semi-dwarfs tend to range 10-16’, and standard fruit varieties are usually considered to be 18-25’.

There are exceptions, such as peaches that are naturally already fairly compact at 12-15’ and cone-shaped pears with a spread of just 10-12’ but a height upwards of 20’ for mature standard varieties. Some standard trees are also just smaller, such as plums and figs.

Part of planning the size we want is planning for space around a tree or shrub where we can work. As a permaculturist, I love stacking spaces and full canopies. However, there’s not much room to maneuver underneath a dwarf or semi-dwarf tree – their canopies tend to start around thigh and shoulder height – and it’s not like all standards are roomy below the canopies. I can create a planting plan that allows me to maximize the space I have without encircling each and every single tree with a path, but somewhere through there, I do have to give myself room to harvest and rake and prune.

Dwarf and semi-dwarf trees produce the same type and size fruit as standards, just less per tree.

Dwarf and semi-dwarf trees produce the same type and size fruit as standards, just less per tree.

Yield By Size

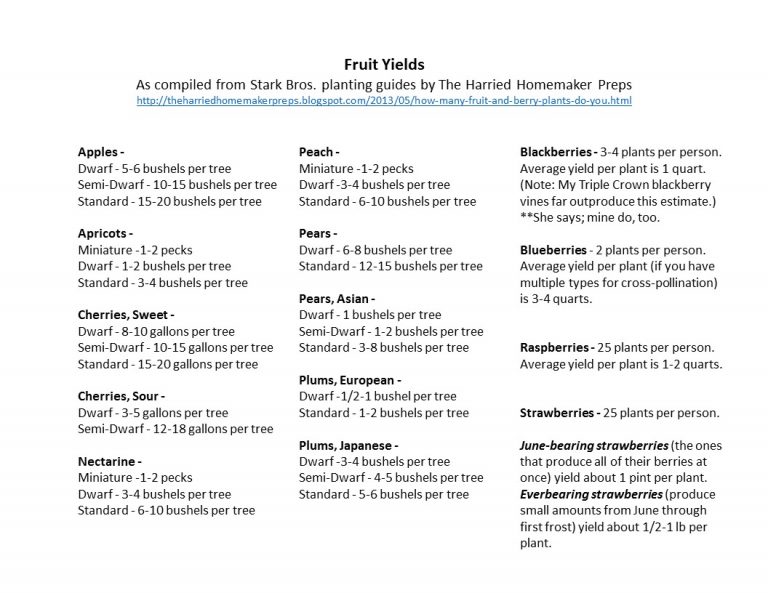

A nice lady who ran a blog once went through and compiled yield ranges from the information Stark Bros. puts out. I turned it into a single-page printable for clients (with citations). As with any, this information should be taken with a grain of salt. Climate, soils, care, and disease can all affect yield, and yield can vary greatly by variety within a species. Still, it makes a nice printable to use for a ratio comparison between dwarf, semi-dwarf and standard trees.

Be aware: Yields vary depending on soil types, nutrients, water, pests, pruning and variety of tree within each species. I halve the numbers from Harried Homemaker and Stark Bros. when presenting estimated to clients.

Be aware: Yields vary depending on soil types, nutrients, water, pests, pruning and variety of tree within each species. I halve the numbers from Harried Homemaker and Stark Bros. when presenting estimated to clients.

Remember, locally produced trees and shrubs, even grafted, will have more success than shipped-in specimens most of the time.

Specialty Types

There are all sorts of even smaller fruit trees and ways to tailor fruits to our needs. Espalier can be done against walls and fences, or grape style in the middle of a yard. Some fruits that are commonly produced on trees have a bush variety, such as the bush nectarine or some of the bush cherries. There are also potted varieties of a lot of fruits now, trees to shrubs and brambles, specimens specifically bred and designed to thrive in a container and be more compact.

Cordon or columnar fruit is available in several species, and while expensive, it can save space to increase diversity and allow homeowners variety and resilience.

Cordon or columnar fruit is available in several species, and while expensive, it can save space to increase diversity and allow homeowners variety and resilience.

Columnar or colonnade trees are extremely narrow and small. They can be potted or directly planted. Their yield suffers due to their size, but they can be excellent as canary varieties for us and they excel at providing some backup pollinators, especially for folks in small spaces or who want edible beautification. However, they are pretty darn pricey.

Container fruit needs a lot of water and nutrients over the seasons, but if we stick them on rolling casters, it lets us maneuver our fruit into protected areas. Those minis can allow us a sustainable source of things like citrus, tea, figs, and peaches. Likewise, an espalier against a wall will typically be warmer as well as easier to protect and keep damp than a freestanding tree in a yard.

Dwarf, container, trellis and espalier fruit can transform a compound into a more pleasant space, allow perennial production in urban and suburban environments, and let us take our fruit trees and shrubs with us when we move.

Dwarf, container, trellis and espalier fruit can transform a compound into a more pleasant space, allow perennial production in urban and suburban environments, and let us take our fruit trees and shrubs with us when we move.

Yard-planting container-intended columnar, bush and espalier fruit has particular application not only for those who are spacially challenged in their yards but for those with compounds. There’s no reason our castle has to look industrial. In fact, back when castles were in vogue, they typically made use of every inch with plantings, which were tailored both for form and function.

Benefits of Smaller Specimens

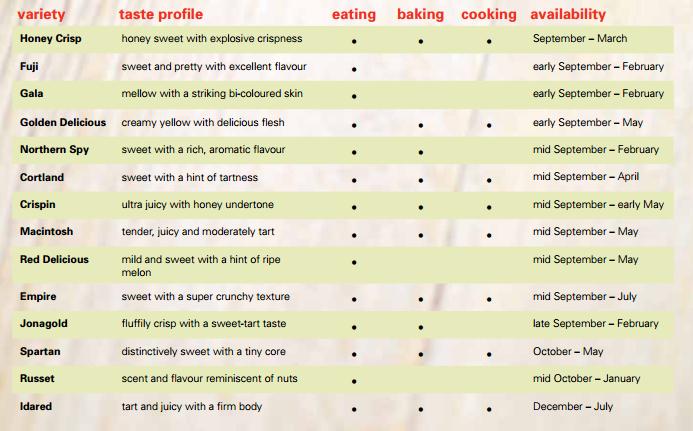

Increases harvest season – One benefit to smaller trees is that we can spread out the harvest season. The common standard tree yields of 10-20 bushels is a lot to deal with inside the 1-3 weeks of the harvest season for each variety, and once it’s in and processed, there’s no more fresh fruit. Instead, we can tailor our home orchard for 3-6 months of fresh produce by selecting varieties from late, mid and early seasons within their species and having a couple of other species with them.

Increases harvest season – One benefit to smaller trees is that we can spread out the harvest season. The common standard tree yields of 10-20 bushels is a lot to deal with inside the 1-3 weeks of the harvest season for each variety, and once it’s in and processed, there’s no more fresh fruit. Instead, we can tailor our home orchard for 3-6 months of fresh produce by selecting varieties from late, mid and early seasons within their species and having a couple of other species with them.

Spreads out the workload – Avoiding a single-type glut such as can come from even just 1-2 large trees (or species) by tailoring our home orchards by harvest period can let us select varieties that go straight to storage to complete the sweetening and softening process, while still having some fresh fruit now. Since summer and autumn are already hectic seasons for a lot of us and will be more so if we’re producing our own food, it’s nice to have that option. Even without storage fruit, smaller amounts harvested over 1-3 weeks per species lets us process fruit at a slower, steadier, more manageable rate.

Easier Management – The workload from processing harvest isn’t the only thing that goes down. Smaller trees allow us to work around them with less use of overhead tools. They’re easier to harvest and prune with only a step stool, and it’s easier to see what’s going on in the canopies. That alone can help us spot problems early.

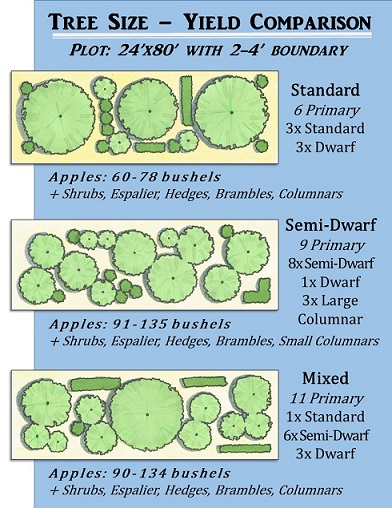

Increase variety and species within a space – Instead of having three apples in standard sizes, we may be able to fit 5-9 dwarf and semi-dwarf trees, in addition to any wall-hugging espaliers and the super-compact minis or potted varieties. Sometimes that means we can get two pollinators for a primary semi-dwarf, and sometimes that means we can have a pair of small apples with a plum and a peach. Other times it means we can have a fruit tree or five, and still have sunlight and space for other perennials or an annual garden.

Smaller trees can allow us to increase variety and resilience in the same space. If one species, variety, or specimen is lost or damaged by pests or weather, others may survive.

Smaller trees can allow us to increase variety and resilience in the same space. If one species, variety, or specimen is lost or damaged by pests or weather, others may survive.

Fresh eating is always healthiest, and having multiple harvest seasons from a variety of trees helps increase the periods of fresh produce, especially if we’re not gardening yet or a drought or the power/labor supply is making us choose between livestock and gardens for water. A variety in fruit types also provides a wider array of nutrients than having just 1-2 trees that produce all at once.

Increases resilience to varying weather conditions, climatic change and pests – Diversity is always a benefit in many ways, but in this case, it’s tangible. A lot of our fruit trees share pests and diseases with each other and other plants, and many require pollination.

If there are only two varieties of apple (or other species), and one is sensitive to something around us, the other has lost its pollinator. We won’t get any more fruit. If we get a semi-dwarf or a single standard for the tree we want most, then 3 smaller trees that cross pollinate, losing one of them to a pest/disease and one of them to weather (drought to storm) still leaves us with a pollinator. We still get our fruit harvest from our target tree. If we had 5-7 smaller trees and lose 2-4, we increase our chances of good harvest in harsh conditions even further.

Graphic: Using a mix of semi-dwarf and dwarf trees can increase the total fruit yield in a space as well as create resiliency. *Yield estimates taken from Harried Homemaker Preps’ compilation of Stark Bros. estimates.

Graphic: Using a mix of semi-dwarf and dwarf trees can increase the total fruit yield in a space as well as create resiliency. *Yield estimates taken from Harried Homemaker Preps’ compilation of Stark Bros. estimates.

The resiliency benefits extend beyond pollination partners. An early-season fruit tree stands more chance of having late frosts and freezes or false springs kill off the buds. Summer storms, bug/pest seasons, and late storms and frosts can all become risks as well. With 3 smaller trees instead of one large tree, we can still get a harvest if one fails or if we lose a tree entirely, inside a species or by planting a variety of species.

Whether they’re small or not, having multiple varieties and species can help avoid total losses and it can help us spot problems early enough to save a harvest. Even if we don’t catch something for the first variety or species, because so many pests are common within domestic fruits, we may be able to treat later-blooming and later-fruiting specimens.

Faster Maturation – Most dwarfs and semi-dwarfs will begin production and hit average, mature rates in less time than standards. Their ultimate total yields are lower, although that can be mitigated with multiple trees.

Future Moves – Dwarf and mini fruit that can handle containers is also beneficial for those who plan to move to a new, larger space or compound. Some of us just can’t justify putting fruit into our small spaces, then leaving it. We can also go ahead and get our fruit trees the day we move, with the plan to transplant once we study and develop our plan for our homestead. That way we’re a little (or a lot) closer to our mature production rates when we hit our new locations.

Small Trees for Big Spaces

Small fruit trees can also be used as “canaries” a la mine-shaft mode, especially on large spreads. We can tuck a sampling of dwarf and super-dwarf compacts in similar light, water and soil conditions along our driveways and near our homes. Doing so lets us keep better track of flowering, health, and fruit development, especially in our busy daily lives, since we see them right there, all the time.

Dwarf and espalier fruit can be trained to hedges, serving multiple functions on our property as well as producing food.

Dwarf and espalier fruit can be trained to hedges, serving multiple functions on our property as well as producing food.

We still need to check on orchards – especially if they’re planted in blocks of the same species or close cousins. Differing microclimates may (will) produce fluctuation even within members of the same species. The diversity of fruit species and other landscaping and gardening can protect our canaries, and lower compaction might be leading to better soil health in one spot or another. Then there are things like chickens, goats, pigs, deer and porcupines that can be affecting outlying trees but not the ones where our dogs and people run most frequently.

Still, over a few seasons, we’ll pick up on the trends and be able to use our canaries to tell us what’s going on in an orchard or even just a few trees that are out of sight-line.

Small Trees for Home Orchards

A small fruit tree isn’t always the solution. For larger families and groups, and anyone interested in silvopasture or sticking crated/kenneled livestock under trees, standard varieties may be a better choice. For those who are looking at age, physical ability, resilience, and small spaces for an edible orchard, smaller trees and container fruits may be a major boost to our capabilities. Smaller trees can also just be faster and easier to care for than large trees, and provide a variety of fruits sooner and a longer harvest period for a busy working family, which may better serve some people.

Dwarf Trees – When Less is More We spend a lot of time looking at annual crops and gardens, but perennials have their places. When it comes to fruit trees, we

Tibby The Barn Cat With A Very Aggressive Cancer

Tibby The Barn Cat With A Very Aggressive Cancer A Sick Ewe

A Sick Ewe Where To Place Bullet In Cattle

Where To Place Bullet In Cattle Bullet Placement In A Pig

Bullet Placement In A Pig